Introduction:

In the annals of India’s economic landscape lies a chapter marked by controversy and clandestine manoeuvrings in the allocation of coal blocks. The year 2015 witnessed the unveiling of a scandalous narrative, revealing the Union government’s egregious denial of West Bengal’s right to bid for the Sarisatolli coal block during the inaugural auction of coal mine blocks. This revelation, borne out of meticulous document scrutiny, sheds light on the covert collusion between private entities and governmental bodies, tarnishing the facade of fairness and transparency.

The allocation of coal blocks has long been a contentious issue in India, marked by allegations of corruption, favouritism, and regulatory lapses. In 2014, the Supreme Court intervened to address these concerns, declaring the allocation of coal blocks since 1993 as arbitrary and illegal. Subsequent reforms aimed to introduce transparency and fairness in the allocation process, emphasizing competitive auctions and imposing penalties for past irregularities.

However, recent revelations suggest that the implementation of these reforms has been marred by controversy and allegations of misconduct. One such case involves the denial of West Bengal’s participation in the auction of the Sarisatolli coal block, raising questions about the integrity of the process and the influence of corporate interests.

Background:

The Sarisatolli coal block, with reserves of 83 million tonnes, was among the coal blocks scheduled for auction as part of the government’s efforts to reform the coal sector. The RP Sanjiv Goenka Group, a prominent corporate conglomerate with interests in various sectors, including power, IT, education, retail, and media, was keen on acquiring the block.

However, documents reveal that the Union government unlawfully barred West Bengal from participating in the auction, effectively eliminating potential competition for the coal block. This decision was based on the government’s interpretation of the eligibility criteria, which disqualified West Bengal due to its prior allocation of illegal coal blocks.

The Role of West Bengal:

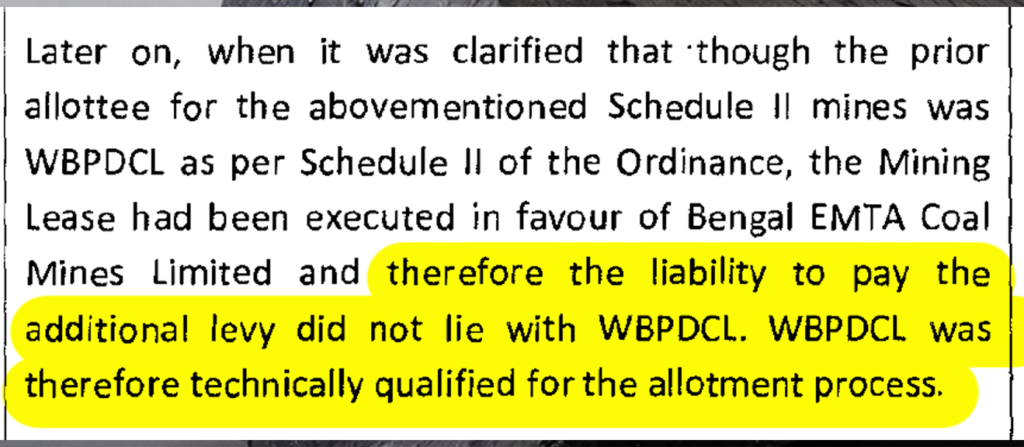

West Bengal Power Development Corporation Limited (WBPDCL), a state-owned company, sought to participate in the auction of the Sarisatolli coal block, recognizing its strategic importance for the state’s energy security and economic development. However, the Union coal ministry disqualified WBPDCL, citing its prior allocation of illegal coal blocks during the period deemed arbitrary by the Supreme Court.

While WBPDCL argued that it had leased the allocated coal blocks to a joint venture with a private company, EMTA Coal Limited, and thus was not liable for the additional levy imposed by the Supreme Court, the government’s decision remained unchanged. This exclusion effectively paved the way for the RP Sanjiv Goenka Group to secure the coal block without facing significant competition.

Controversies Surrounding the Auction:

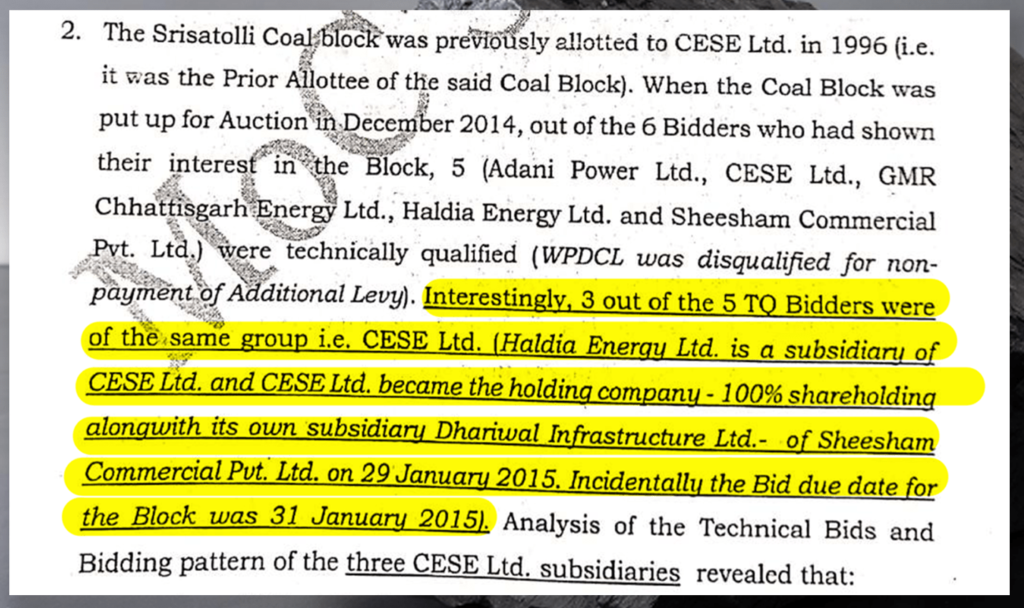

The subsequent auction of the Sarisatolli coal block raised eyebrows, particularly due to allegations of collusion and rigging among bidders affiliated with the RP Sanjiv Goenka Group. A confidential audit conducted by the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) highlighted irregularities in the bidding process, including the involvement of multiple bidders from the same conglomerate and breaches of bid secrecy protocols.

Despite these concerns, the government defended the integrity of the auction, pointing to the number of qualified bidders and the competitiveness of the process. However, critics argue that the exclusion of West Bengal from the auction undermined the fairness and transparency of the process, allowing corporate interests to prevail over public welfare.

Legal and Ethical Implications:

The case of the Sarisatolli coal block raises broader legal and ethical questions about the allocation of natural resources and the accountability of government institutions. The Union government’s decision to deny West Bengal’s participation in the auction, despite acknowledging its eligibility, highlights the discretionary power wielded by policymakers and the potential for regulatory capture by vested interests.

Moreover, the government’s failure to address the concerns raised by the CAG audit underscores the lack of transparency and accountability in the allocation process. By allowing the RP Sanjiv Goenka Group to retain control of the Sarisatolli coal block despite evidence of misconduct, the government risks eroding public trust in democratic institutions and perpetuating a culture of impunity.

Recommendations for Reform:

To restore public confidence in the allocation of natural resources and ensure fairness and transparency in the process, several reforms are necessary. First, there must be greater clarity and consistency in the eligibility criteria for participating in auctions, with clear guidelines for determining liability for past irregularities.

Second, regulatory bodies such as the CAG should be empowered to conduct independent audits of allocation processes and investigate allegations of misconduct thoroughly. Any findings of irregularities or collusion must be promptly addressed, and appropriate action taken against those responsible.

Finally, there should be greater public oversight and engagement in the allocation process, with mechanisms for transparency, accountability, and stakeholder participation. Civil society organizations, the media, and concerned citizens play a crucial role in holding government institutions and corporate entities accountable for their actions.

Conclusion:

The case of the Sarisatolli coal block highlights the challenges and complexities inherent in the allocation of natural resources in India. While reforms aimed at introducing transparency and fairness are a step in the right direction, their effectiveness depends on robust implementation and enforcement mechanisms.

By addressing the legal and ethical implications of the Sarisatolli case and implementing meaningful reforms, India can strengthen its democratic institutions, promote sustainable development, and uphold the principles of justice and equity. Only then can the allocation of natural resources truly serve the interests of all stakeholders and contribute to the country’s progress and prosperity.